Preparation and Listening: The Foundation of Effective Workflow

In any collaborative effort, success begins long before tasks are executed. The first quadrant of effective workflow—Preparation and Listening—focuses on clarifying concerns, assessing relationships, and setting the stage for meaningful action. By listening deeply and preparing thoughtfully, individuals build the trust and alignment needed to move forward with confidence.

This is Article 2 in a five-part series that explores the application of Effective Workflow practices. Explore the other articles:

► 1- Understanding workflow: A new paradigm for effective collaboration

► 3- Assessments and Negotiation: Crafting Mutual Commitments in Workflow

► 4- Execution and Performance: Delivering on Promises in Workflow

► 5- Value and Learning: Closing the Loop in Workflow

by Stewart Ramsay and Peter Claghorn, Vanry Associates

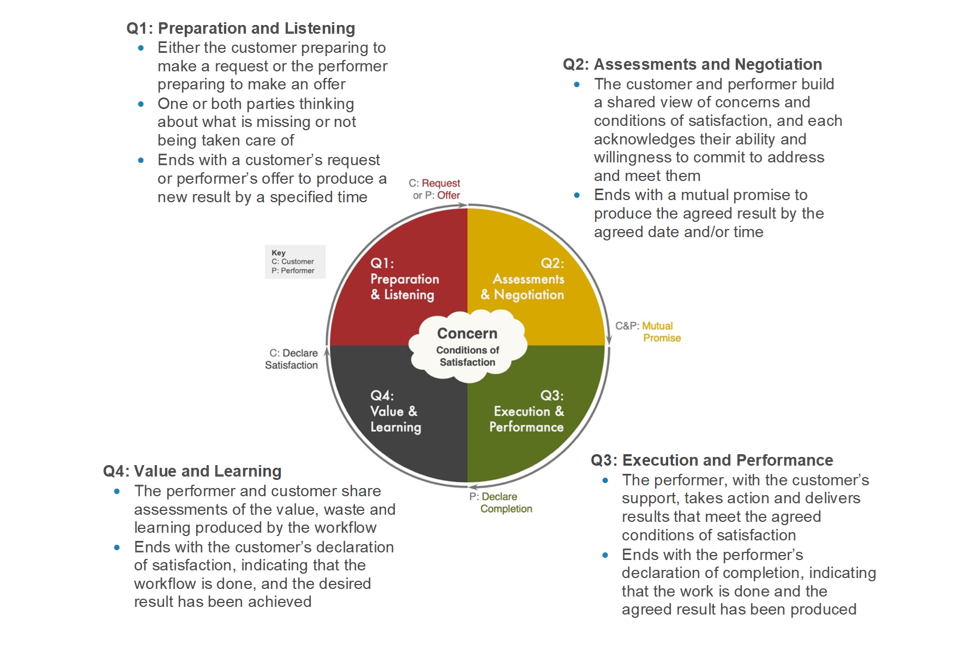

In the hustle of daily work, it’s easy to see tasks as isolated items on a to-do list, checked off one by one. Yet, work is rarely a solo endeavor. It’s a dynamic conversation between people striving to create a shared future, driven by what matters most to them. The workflow model, a universal framework for coordinating action, captures this reality by breaking work into four interconnected quadrants.

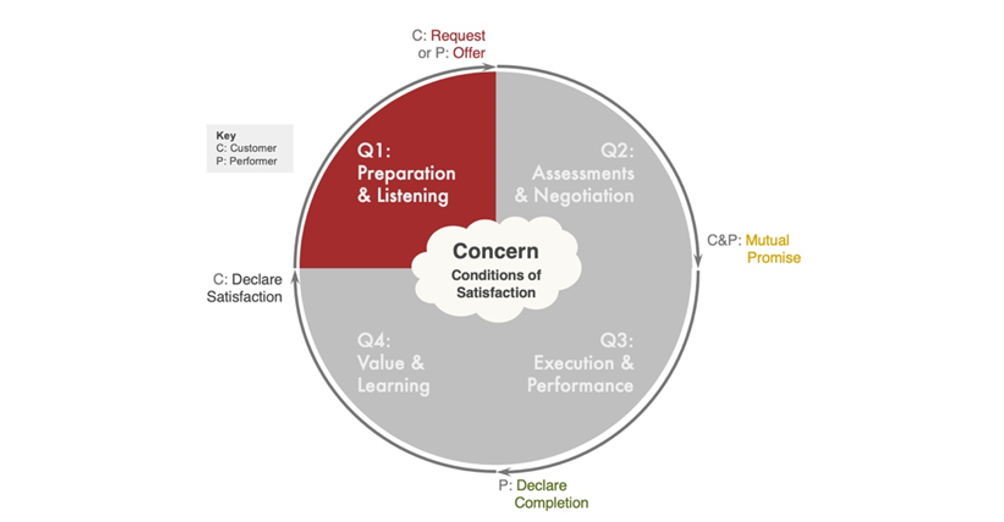

The first, Preparation and Listening (Q1), is where every successful collaboration begins. This phase is about understanding what’s at stake, assessing whether the relationship is strong enough to support the work, and laying the groundwork for mutual value. By mastering Q1, individuals can transform routine interactions into productive, trust-building exchanges that set the stage for meaningful results.

At its core, Q1 is about listening deeply and preparing thoughtfully. It’s the moment when a customer—the person with a request or need—articulates what they care about, and a performer—the one who will deliver—evaluates their ability to fulfill that request. Unlike other phases that focus on action or outcomes, Q1 is about possibility. It’s where the seeds of trust and alignment are planted, ensuring the workflow doesn’t falter later due to misunderstandings or misaligned expectations. The document Effective Workflow describes this as a phase where “people listen to each other and mull over the possibilities for engaging with each other,” culminating in either a request from the customer or an offer from the performer.

The concept of “concerns” is central to Q1. Concerns aren’t fleeting wants or worries; they’re deep, often unspoken cares that drive action. For example, a manager requesting a report isn’t just asking for data; their concern might be ensuring a project stays on track or maintaining credibility with stakeholders. Similarly, a parent bathing their children is driven by concerns for health and social reputation within their community. The customer’s job in Q1 is to provide enough context so the performer understands why the request matters. This means sharing the “why” behind the request—its purpose, priorities, and broader implications. Without this clarity, the performer may miss the mark, leading to wasted effort or misaligned outcomes.

For the customer, Q1 involves more than just stating a need. It requires assessing the performer’s competency, mood, and authority to deliver. Imagine a manager asking a junior employee to prepare a complex financial analysis. The manager must evaluate whether the employee has the skills and resources to succeed. If not, the manager must either provide support or choose a different performer. The document emphasizes that “if the customer is committed to making this request of someone who is not fully competent, their responsibility to support the performer throughout is increased.” This assessment isn’t just about technical ability; it includes the performer’s mindset. Is the performer distracted or unmotivated? Do they have the political authority within the organization to act effectively? These factors can make or break the workflow.

The performer’s role in Q1 is equally critical and revolves around active listening. They must discern the customer’s concerns, often picking up on cues beyond words, like tone or hesitation. For instance, a consultant offering a service to a client must listen for what matters most—perhaps the client is prioritizing speed over perfection. The performer also assesses their own capacity: Do they have the skills, time, and resources to deliver? If not, they must be honest, either declining the request or proposing an alternative. The document advises performers to “make responsible assessments of own competence and capacity to deliver,” as overpromising can erode trust and lead to breakdowns later. When making an offer, the performer shapes it to align with the customer’s concerns, ensuring the proposed action creates value.

A key metaphor in Q1 is the “relationship bowl.” Every workflow requires a relationship strong enough to hold the transaction, like a bowl containing soup. A small bowl works for simple tasks, like ordering a coffee, but complex tasks, like collaborating on a major project, require a larger, more robust bowl. The document warns that an insufficient relationship leads to waste—think excessive paperwork, misunderstandings, or broken promises. Conversely, a sufficient relationship enables flexibility, trust, and even “doing business on a handshake.”

For example, scheduling a car service appointment involves a small relationship between the customer and the service representative. The customer shares their concern (e.g., a reliable car), and the representative confirms availability. If trust is low, the interaction may require detailed confirmations, slowing the process. A stronger relationship allows for smoother coordination.

Practical application of Q1 principles can transform how we approach work. Active listening is paramount. Customers should ask themselves, “Have I clearly explained why this matters?” and performers should ask, “What is the customer really caring about here?” Observing non-verbal cues, like a hesitant tone or rushed demeanor, can reveal unspoken concerns. For instance, a client who emphasizes deadlines repeatedly may be worried about external pressures, signaling the performer to prioritize speed. The document suggests that “concerns are often illuminated through patient listening and reflection on the sum total of our interactions with the person.” Asking open-ended questions like “What’s most important to you in this project?” can uncover these concerns.

Another practical tip is to assess the relationship’s sufficiency early. If you’re a customer, consider whether you trust the performer to deliver without micromanaging. If you’re a performer, reflect on whether the customer’s authority and clarity make the task feasible. If the relationship feels strained—perhaps due to past misunderstandings—take steps to strengthen it before proceeding. This might mean a quick conversation to clarify expectations or acknowledge past successes together. The document notes that “one of the best ways to improve your ability to work with someone is to expand the size of your relationship,” which starts in Q1.

Mood also plays a significant role in Q1. Both parties should approach the interaction with a productive mindset. A customer who’s frustrated or unclear can derail the workflow before it starts, while a performer who’s disengaged may miss critical details. The document advises assessing “mood and political authority appropriate to being successful in the request.” For example, a performer who feels undervalued may hesitate to commit fully, so the customer might need to foster a sense of partnership first.

Diagnosing Q1 issues can prevent future breakdowns. The document’s checklist asks customers to ensure they’ve provided sufficient background and assessed the performer’s capacity. Performers should verify they’re engaging with a productive mood and have the resources to deliver. If a workflow falters later, revisiting Q1 can reveal missing elements, like unclear concerns or an inadequate relationship. For instance, if a project stalls because the performer misunderstood the customer’s priorities, the root cause may lie in Q1’s lack of clarity.

To illustrate, consider the car service example from the document. When scheduling an appointment, the customer (you) calls the dealership and explains their concern: a reliable car for an upcoming trip. The service representative (performer) listens to confirm availability and assess whether they can meet the timeline. Both parties evaluate the relationship—can the customer trust the dealership’s reliability? Can the representative rely on the customer to provide clear information? A successful Q1 interaction ensures the appointment is set with mutual understanding, paving the way for the service to proceed smoothly.

Q1’s power lies in its ability to align people before action begins. By focusing on concerns, assessing capabilities, and ensuring a sufficient relationship, both customer and performer create a foundation for success. This phase isn’t about rushing to action but about pausing to listen and prepare thoughtfully. As the document states, “keeping the central concern of the workflow apparent to the customer and performer increases the likelihood of a satisfying and valuable transaction.”

In conclusion, Preparation and Listening is the bedrock of effective workflow. It’s where trust is built, concerns are clarified, and relationships are sized for the task ahead. By mastering Q1, individuals can ensure their workflows start strong, setting the stage for the commitments and actions to come in Quadrant 2, Assessments and Negotiation. Whether you’re scheduling a car service or launching a major project, Q1 is your chance to get it right from the start, turning conversations into coordinated, value-driven results.

Banner & thumbnail credit : AI generated image by Steph Meade on Lummi