Our assessments and assertions and how they impact our moods

We often think about moods as something that happens to us, out of our control. We see or hear something that puts us in a ‘bad mood’ or see or hear something and find ourselves in a ‘good mood’. Over years of study as leaders in human relationships, we are able to see that our moods are a product of our own thinking.

By Stewart Ramsay, Vanry Associates

We suggest another interpretation of mood: as particular emotions, with associated patterns of thinking that take root over long periods of time, and are in the background of our awareness, often invisible to us. Our mood is the long-term emotional tenor of our life, affecting all we observe and do. An emotion, on the other hand, moves through us, lasting a few moments — unless we think thoughts that keep generating it over and over for days or weeks.

We are always immersed in a mood, never free of one. This phenomenon may make it challenging for us to be aware of our mood; a kind of cognitive blindness. We might say ‘moods have us’ as opposed to the commonly used ‘they are moody.’

We experience the world around us from inside our mood. They don’t our reality, our mood and our reality are the same; as we perceive, so do we ‘observe.’ Our mood is a predisposition to act. Through the lens of mood, certain futures are possible, others are closed.

Our Mood brings a state of enhanced readiness to experience particular emotions. If we are generally in a mood of resentment, we are more ready to feel frustration rather than acceptance when something goes awry.

Our mood is more than a private mental or psychological state — it forms a significant part of our public identity. Others experience us through our words and actions, which are influenced by our moods. Their views of us inform choices they make about how they might interact and undertake work with us.

Morale, a common business reference, is a community experience. Although we live inside our own mood when we recurrently interact with others, a group emerges with its own unique mood, or morale.

Mood is highly contagious, with positive benefit or negative impact. Many people might assume that their mood is ‘caused’ by situations around them, believing they have no choice in the matter. This assumption is self-limiting. It assumes we are ‘at the whim’ of others; unable to generate our own mood. It concedes control of our mood, rather than retaining control for ourselves. Consider instead if we may suddenly find ourselves in a mood we did not choose, it is our responsibility to shift to one more useful.

Our mood may be productive or unproductive, meaning it supports us moving forward or impedes our progress, keeps us stuck. On the productive side, we are confident and resolved to produce results. When unproductive, we may be overwhelmed, feel frustrated, and cannot seem to make progress.

We can change what we are aware of, make choices, and thus, move through unproductive to productive space.

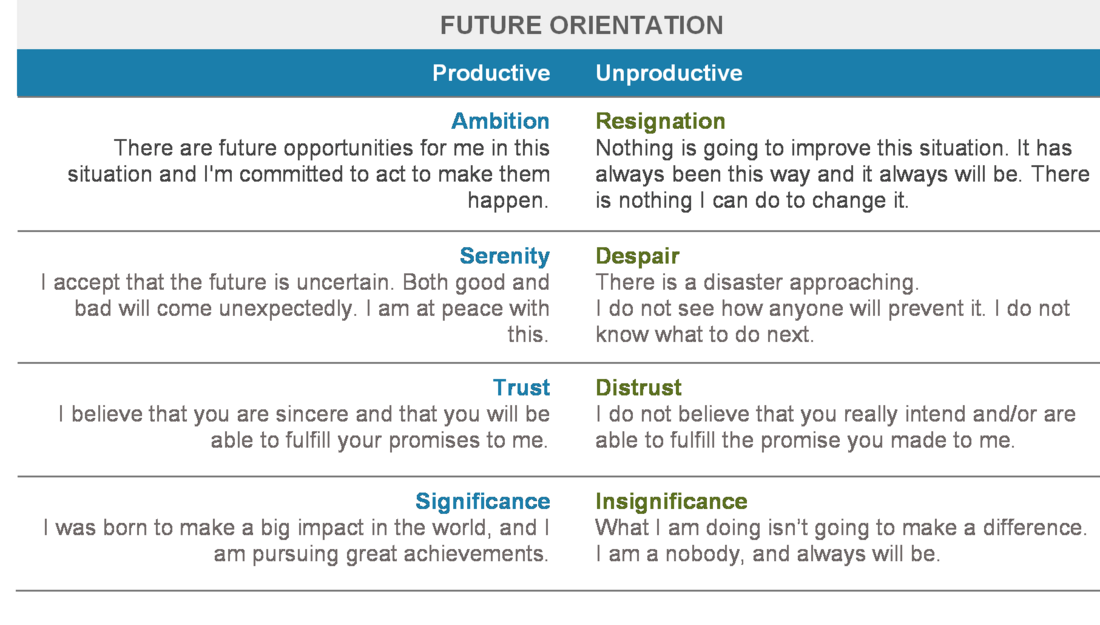

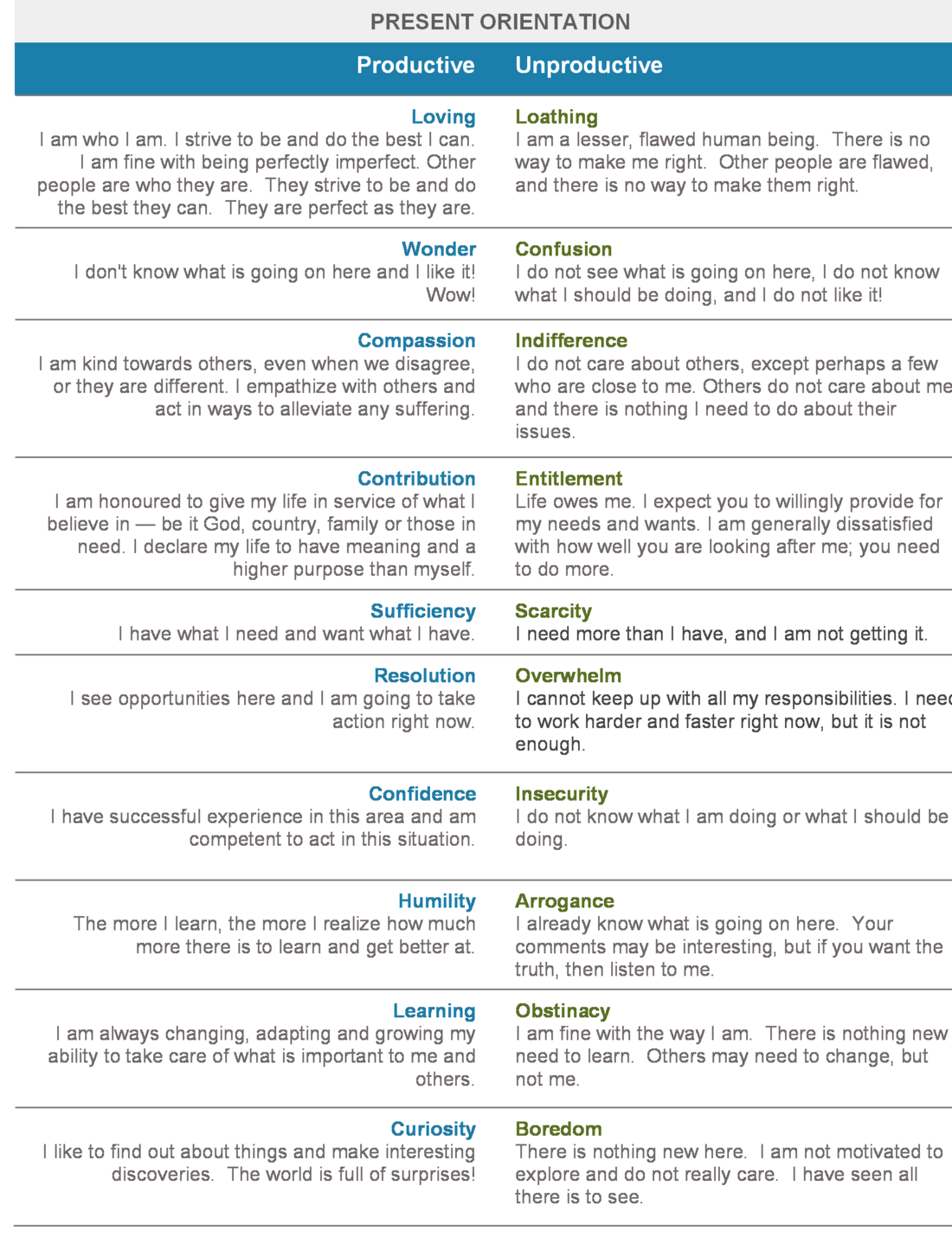

The following are common moods, occurring in pairs [1] presented against typical future or past orientation. The terms productive or unproductive are intentional and represent useful, of value, versus not useful, producing waste. Some pairings may be present for long periods, (years, decades) becoming a predominant mood for individuals.

Options for improving mood

We believe moods reside in our bodies as automatic, largely transparent, emotional and linguistic patterns, that are contagious and changeable.

We experience life inside our moods, whether we embrace or resist the past, the present moment, or the future. Our moods shape what actions we take and how well we perform going forward. They free or constrain us, support us, or leave us diminished.

We believe we can improve our own moods and those of others. We can create and sustain the productive side of mood by being aware of and intentional in the narratives we create. We can be accountable for influencing the moods of others positively. We can use practices to support productive moods, individually and collectively.

Shifting our own mood to be more productive

It is our accountability to be in the productive side of our mood more frequently and to sustain it longer. Our goal is not to be 100% in the productive side of our mood; that is unrealistic. Our goal is to recognize when we begin shifting to an unproductive side and return as quickly as we can to the productive side.

- A reasonable goal is to return to our productive side within minutes versus days, weeks, or years of staying unproductive.

- The productive and unproductive sides are equally robust and strong.

So how do we shift our mood? First, we recognize that it’s our reactions to assessments and declarations that is most impactful on our mood. Accepting that, we then need to notice when our mood has shifted, stop and think:

- “What thought just ran through my head that affected my mood?”

- “Is the mood productive or unproductive? What do I want to do about it?”

- “What different assessment or interpretation could I have about the situation that would serve me better, shift my mood?”

Simple explanation, not simple to do. Doing it produces immediate results. It requires practice, patience, and repetition to create an automatic habit, noticing and shifting your mood.

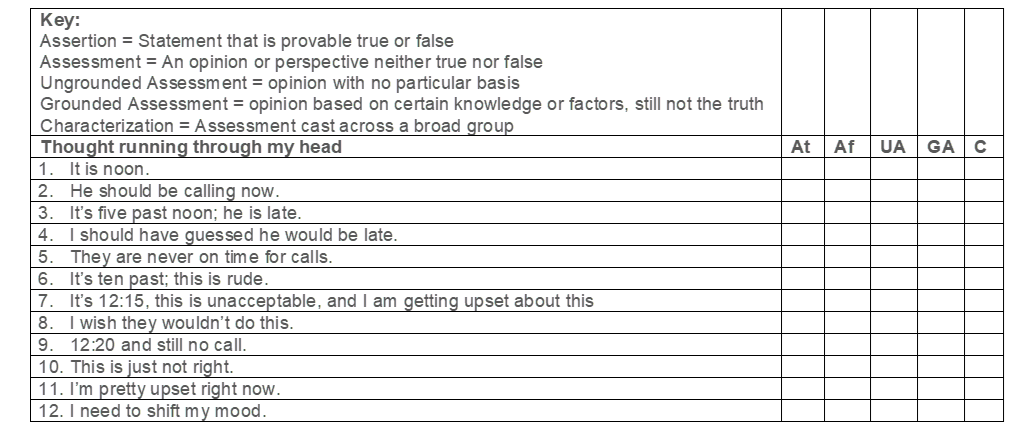

Consider the following example:

I called a client Friday with urgent information, just as they were leaving and uncontactable until Sunday. We agreed to speak at noon, Sunday. We confirmed time differences between our locations.

Sunday, at my desk ready, noon approached and passed. Several thoughts ran through my head (table below). Using the key, define each of the thoughts?

What do you notice over the 20 minutes about the:

- Thoughts?

- Mood?

- Conversation taking place?

- Linkage between assessments and the mood emerging?

This happened during the switch from Day Light Savings to Standard Time, and by the clock on my computer screen, it was only 11:21AM. 39 minutes until the call time. The client hadn’t done anything wrong.

Some of the things that we can see from this example:

- The “Assertions” about the time were untrue.

- I did not ground the assessment of “he is late” sufficiently well to expose the erroneous assertion.

- Grounding does not increase the validity of an assessment.

- Not all Assertions are true, even if we believe them.

- I created my Mood. It was perturbed by an outside event, a meeting request, and my assessment that the client was late.

- I was having conversations with my assessments and allowing them to impact my mood.

Note that many of the assessments I ended up making were from a background mood of resentment of past lateness. My mood was influenced by my assessments, and my mood!

In the end I laughed at myself, realizing this case was evidence that our assessments lead our mood.

I made a new set of assessments and shifted my mood.

Thumbnail & banner credit: Jason Leung sur Unsplash

- [1] This interpretation is from the work of Dave Hawkins of VANRY Associates and builds on the distinctions from Gloria Kelly of the As-One Group in “About Morale”, May 1999 and Dr. Fernando Flores, “Morale, Trust and Partnership”, BDA 1991.