Guidelines for safe work methods in substations

This Technical Brochure provides guidance for working safely during construction, inspection, maintenance and operation. The research by the WG discovered that despite intense efforts and improvements by utilities and contractors in recent years, accidents still happen. The TB provides a collection of examples and best utility practices from around the world. The key to a safer substation workplace is a design that can control the outcome plus empowering and supporting everyone when identifying unsafe activities.

Convenor

(US)

M. MCVEY

Secretary

(GB)

J. NIXON

K KAWAKITA (JP), T. ABE (SG), E. BURT (CA), G. BUCHS (CH), A. CALAZANS (BR), J. CAMDEN (US), A. CHEANG (SG), F. FRAGA (BR), M. FURUYA (JP), J. HUISMAN (NL), A. ILO (AT), M. KATSUMATA (JP), L. KORPINEN (FI), J. MEEHAN (CA), A. OKADA (JP), S. RUNGKHWUNMUANG (TH), D. QUINN (IE), J. RANDOLPH (US), I. ROHLEDER (CH), S. SAMEK (PL), S. SHOVAL (IS), G. TREMOUILLE (FR), I. ULLMAN (CZ), A. WILSON (GB)

Corresponding Members: H. CUNNINGHAM (IE), J. FINN (GB), T. KRIEG (AU), K. WILLIAMS (AU)

Introduction

There have been many books, seminars and utility programmes about a safe work environment. Safety manuals are full of rules that represent insight from the past performance of personnel that have been injured or killed. It is important to learn from the mistakes of the past, but trending and analytics will only take an organisation so far. In the last thirty years great strides have been made in safety performance and personal safety in substation work, but the struggle to move to zero accidents for most utilities has hit a plateau. The TB focuses not only on what the industry views as the best practise but also discusses human factors on attitude and performance.

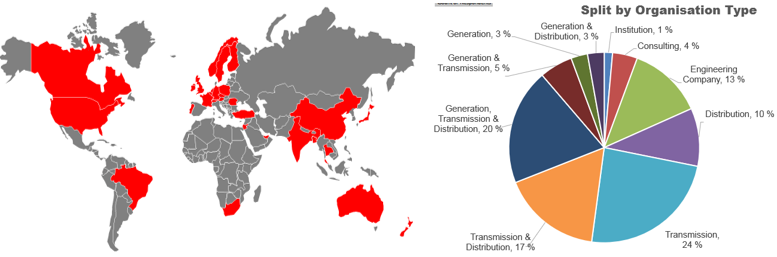

A questionnaire was distributed globally to known experts in utilities, engineering companies, consultants and academia, see Figure 1 for details. A workshop was also held at the CIGRE Paris session in 2018 were 84 global experts collaborated on “Safety Culture” tasks. The information gained from both have been incorporated into the TB.

Figure 1 - Global survey responses and by organisation type

The scope of the TB should provide ideas and topics that the participants in CIGRE across the world view as important for any safety performance. The goal of this TB is to provide guidance on ways of approaching an accident free environment. Design plays an important role in achieving this. Substation design is not just a function of correct electrical clearance but should be about providing a safe work environment. This TB addresses human factors in work and design, and shares a philosophy for the betterment of all, to have a safe working environment for substation construction and operation that ensures safety and wellbeing for all who interact with it.

Guidance is included on concepts of good engineering and safety practices. All phases in the life of a substation are considered, not only when workers are on the substation site carrying out their duties but before anyone ever sets foot on the site. The TB also considers other people, potentially with limited knowledge of the electrical dangers present, who are likely to be on or near the substation during, and post, construction.

Every worker at every level should have the right to say “STOP” when something has changed or is not understood. Management inside and outside the organisation of the party instigating the stop work should be supportive, as continuing beyond this point has the potential to end badly for all concerned.

Structure and content of the Technical Brochure

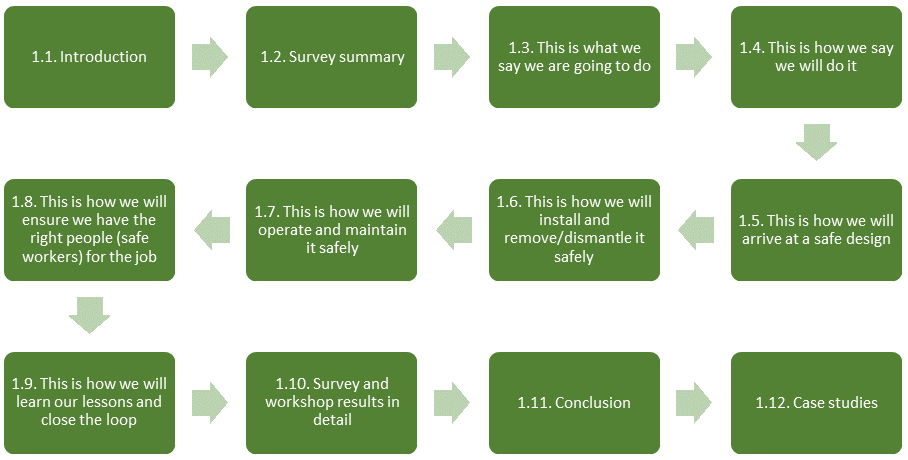

The structure of the TB, see Figure 2, follows the lifecycle of a project and that of the substation:

Figure 2 - TB structure

Before we begin any site work

Looking after the public and the substation workers, no matter what their training or knowledge, is of paramount importance. So before undertaking any physical work, businesses within our electricity supply industry set out their stall; this is what we say we are going to do.

Safety should be a consideration at all stages of a project, not just whilst the work is being carried out but from project inception through to design implementation. Safety aspects can be addressed before the site work stage thus ensuring hazards do not present themselves to site workers. The TB message is not just to reduce risk but also to consider mitigation measures that reduce the potential impact of an accident.

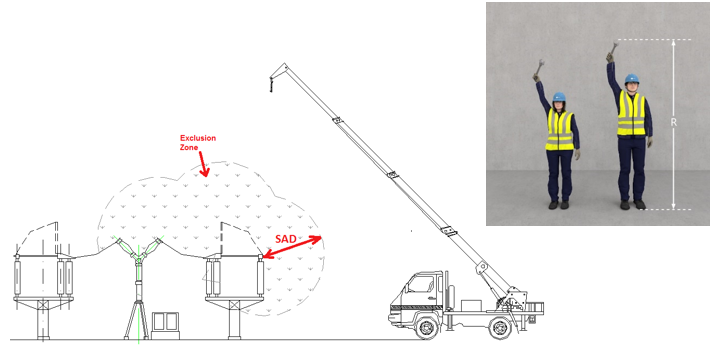

Figure 3 - Safety by Design considerations for e.g. temporary situations and worker variability

Thoughtful focused work is how designers can influence the safety of those who build, operate and maintain the substation. Utilities should employ a “Safety by Design” process for developing the safe design of its substations. The safety by design process should consider all possible scenarios and at all stages. Figure 3 shows types of examples that safety by design considers.

Carrying out the site work safely

In order to implement sitework safely, all workers on site and utilities should acknowledge the risks of the work and remove or mitigate the risks before the work starts. A regular inspection programme is necessary to document the current condition of the substation. The TB provides examples of guidance on important work practices for safe operation and maintenance activities for the life of the substation.

Ensuring we have the right people

Any plan or project that is intended to be safe and successful must have a test for success. An accredited process to train personnel has proven to be instrumental worldwide. Professional preparation has significantly reduced accidents on and off the work site. The process should be rigorous and continuously updated and examined. The TB outlines a process followed by many countries and utilities to train, examine and record worker capability. Safe workers need experience and tools to perform. Skills and methods training must also involve attitude training. A list of activities is presented and should be discussed by utility workers and supervisors to share the best approach to ensure the maintenance process works and data is available to verify results.

Learning lessons and preventing reoccurance

At the end of each project or at the end of each phase of the works all utilities and contractors should go through a “lessons learned” process to evaluate what went well and what should be improved for the next project. It is important to include all stakeholders in the process to capture as much information as possible. Data and KPI’s generated during the works are useful to feed into the lessons learned process.

Actions that result in unsafe work should be targeted and eliminated to ensure they are never repeated. Making actual changes can be difficult. It is the most problematic part of the overall lessons-learned process and, therefore implementing change is the most important part which will require energy, determination and management support to be successful.

Conclusion

The WG believes having safety as the number one priority is essential to ensure the lowest levels of incidents and accidents. This belief has been validated by the answers and feedback received from the survey and the workshop. The WG recognises there is no hazard-free environment. Every work day, wherever we are, we are subjected to hazards that are surrounding us. How we complete the day with no injuries largely depends on our own awareness and taking necessary precautions.

It is not just the management of the organisations that are responsible for the health and safety of everyone, but it must be emphasised that it is every individual who has the responsibility of ensuring he or she is safe whilst ensuring their colleagues around them also remain safe when carrying out their duties. Designers have the ability and duty to eliminate hazards, where possible, preventing them from ever appearing at site.

Adopting a great safety culture needs to become second nature. “Stop work” is a recent introduction to try and promote safer work and to prevent a potential incident occurring. This human performance objective must be supported at all levels of the utility, contractor organisation and the supply chain. At any level within the project organisation, if something looks unsafe or risky, the people involved should ‘stop work’. It must be recognised that intervening and requesting someone or a team to stop work takes courage as it can be intimidating.

The management team in all organisations must be fully supportive of the safe way of working as a core value. It is not good enough to pay lip service to such an important subject. If we truly believe people who come to work each day, should go home in the same physical condition, then it is up to the management organisations to walk the talk and enforce the message that safety is the number one priority.

When we have incidents our first reaction is to amend existing, or introduce additional, procedures. These are “objective” elements. From the endeavours undertaken by the WG evidence would suggest we need to focus more on the “subjective” as incidents are more associated with individuals rather than the systems they follow. Feedback from the Paris workshop members was very “people” biased and not totally “process” driven.

Change, whenever it occurs, can be problematic. When change occurs after the work has started then this can be a potential for an incident. “Change” does not necessarily mean something significant but can be subtle enough to make a real difference to working conditions such as; morning to afternoon, yesterday to today, etc.

Life is precious, the consequence of an accident in a substation can be extreme for ourselves, colleagues, friends and families. Therefore, we all must take care of each other to ensure they do not happen, whether at the worksite or elsewhere. It is down to all of us individually to take ownership of the health and safety of ourselves and others. This TB strives to ensure the welfare of us all.